2014 11 17 • Kalimat Magazine

[original article link]interview by Ali Charrier

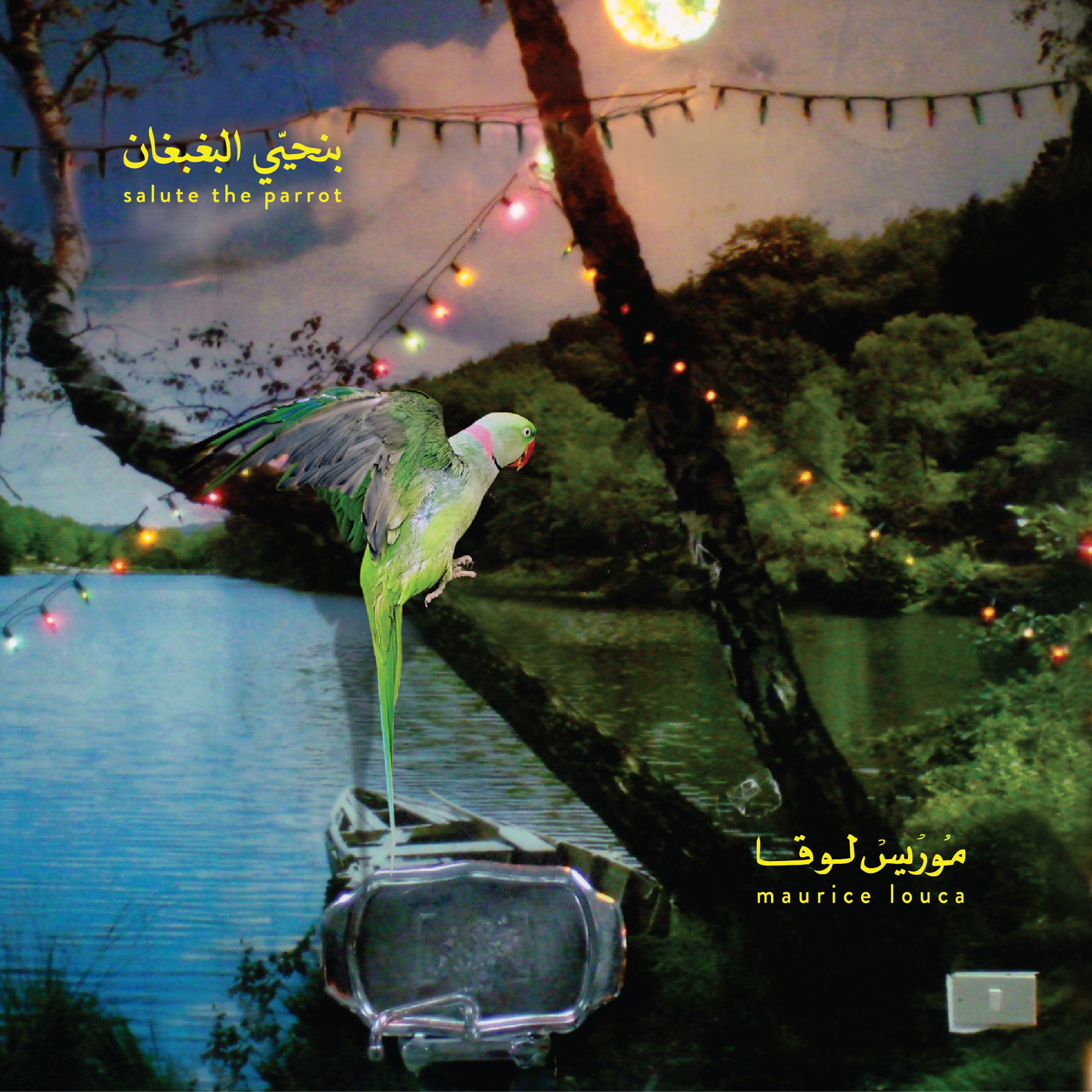

photo by Lars Opstad

Khyam Allami is one of the busiest actors in the Arabic music scene today. If he is not busy rehearsing with his band Alif or organising tours, he is performing solo with the Oud or as a drummer with Tamer Abu Ghazaleh. After years of experience in the music industry, Khyam Alami decided to launch his own record label Nawa Recordings. I had the chance to chat with him in Paris before the show featuring Maurice Louca at La Gaité Lyrique, who is releasing his second album Benhayyi Al-Baghbaghan (Salute the Parrot) with Nawa Recordings, today [17 November 2014].

AC | How long have you been working on Nawa?

KA | I started planning things last December. It has taken me almost a year to get it up and running, since there is a lot to think about from all angles. [Launching] a record label in Europe is really easy - one of the easiest things in the world [in fact]! You don’t even have to register as an official company, you just decide on a name, make a logo, get a barcode, send your stuff to be manufactured, and it’s done. Afterwards, you can sell it at shows, work with CD baby, and distribute and sell online. That element is really simple, but creating a framework that actually runs as a professional label, not just as a home for you to release your own stuff, is much harder work. [You have to consider] the right people to do the PR, the best distribution methods, and finding a model for working that is a bit different because at the end of the day, we’re dealing with new music from the Arab world, which is created with the Arab audience in mind initially. So being able to reach that audience and make your work available to them is difficult. There was a lot of thought that went into that, and how to try new techniques based on methods that are [currently available]. The music industry in Europe has changed a lot, and it continues to develop with new methods, tools, etc., but one of the biggest things that record industry is relying on here is the postal service.

AC | Really?

KA | E-commerce platforms relies on the post. This in the Arab world is still very young. It's extremely difficult to do a mail order style label in the Arab world. There’s no [proper] postage system that to speak of, and you have to rely on international courier companies like FedEx, and Aramex who are very expensive. [It's not feasible] to sell an album for 40 Egyptian Pounds [EGP] and expect the buyer to pay 80EGP on shipping. In Europe, it's easy to pop things in the post.

AC | Is having a record label something you’ve always wanted to do? Can you tell me how you’ve been preparing for Nawa Records?

KA | It has been a dream for over fifteen years. Back in 2003, I set up a label with some friends in London. It was called House of Stairs, and we did four releases in one year, a compilation album called “Useless in Bed”, an album called "Secrets and Signals" by Stars in Battledress, then we [released] an album called “Arm yourself with Clairvoyance” by a band called Foe, and then a split album by a band I used to play in called Art of Burning Water with Foe, and a band from Chicago called American Heritage. A lot of work went into those four releases. [We're talking], four releases in one year for a totally independent label with no money! Back then it was really an achievement. At the beginning it was a community of around 20 people, all the different artists were in all the bands, plus others. But after awhile, the number of people involved kept shrinking, and at the end it was just me and Jason Carty who composed all the music for Foe. We [weren't able to] manage keeping it up, and the scene kind of fell apart; all the bands kind of split up. The idea itself got put on hold, but it has been a dream since then. I tried to do something again in London back in 2010 which didn’t quite work out, but this time I decided I’m gonna go alone [because] there’s so much music out there that I really want to work with and I’m so passionate about making it available properly, and also by helping those artists being able to invest in themselves. Nawa has taken on a very different model to most labels. We only do licensing, we don’t claim ownership of anything, and our contracts are very artist friendly. Basically I created a contract that I would be willing to sign, and I’m not an easy person! It’s based on the old school rough trade model of this very indie, 50/50 split, but it’s not this kind of indie 50/50 split with whatever comes goes. No - there’s accountants, tlawyers, PR, a proper framework for the label to run, and so I hope that this I going to help us all be able to develop because at the end of the day all of us have really great ideas - musical ideas - we have a lot of ambition and energy, and we need to be able to create that to share it with people.

AC | Do you already have your contacts, all your network up and down the chain, from recording to distribution or is it still being put in place?

KA | The fundamentals have been put in place for a while and without them, it’s impossible to launch this project. This is what we are launching now, slowly, and by experimenting with certain ideas things that will develop and change. It’s an entrepreneurial venture so you can’t [predict] what’s going to happen, and I’m stepping into a really saturated market. Labels are everywhere, and the amount of music being released today is unbelievable compared to five to ten years ago.

Khyam performing with Tamer Abu Ghazaleh at Festival Les Suds à Arles

AC | Are you planning to develop an online retail platform?

KA | The online store is the main focus, [where] digital is available of course, but we’re also focusing on local physical distribution in the Arab world. In Egypt, we’re developing a setup where people will be able to order online, and if they order before 3pm, we offer same day delivery. Most of my efforts have been geared towards making the music available, in the sense that people are going to be able to stream it, but actually making the music available officially so that people are able to support the artists that they want to engage with. This is the key thing, and another part of the forward and long-term thinking strategy: how can we allow ourselves as artists – and the artists that Nawa wants to work – with the space to become self sustainable, and be able to reinvest in their own work. This is the strategy I took for my own work with Resonance/Dissonance [Khyam's debut solo record], whether it be equipment, new tools, whether it be in my work or other side projects, everything was being reinvested all the time, no matter how small. If I was lucky enough to be paid 500€ for a show, that money would go into paying for rehearsals, flying out to Cairo to work with Tamer on a show, and at the same time do an Alif rehearsal, or something else. It’s always this kind of kill as many birds with one stone [type of idea].

AC | With Nawa recordings, what areas do you put the most work on? Is it exposure of artists, tour support, helping record, developing repertoires and artists, or creating new acts?

KA | At the moment, it’s all about working with artists who already have a vision, who already have [some] work planned, work in progress, or almost finished. [My aim] is to to help people realise their dreams. As a musician myself, I have a lot of dreams and ideas, and I want to realise them. The same is true of musicians around me, and I want to help them realise those things as accurately and as honestly as possible, whether that would be taking something that is almost finished and just releasing it and making it available, or working with somebody from the very early stages. Obviously there’s a lot of effort on PR also to make sure people know about these things. I’m putting a lot on effort into e-commerce to make sure that we can sell directly to fans, and having that relationship so that we can give the fan base more than just music. There’s quite a lot of focus on distribution, and I will be focusing a lot on tour support, sync licensing, and these kinds of things. It's really a step by step process, we’re just launching and I’m alone in this, apart from the team that I’ve managed to build now, who are freelancers and other independent organisations like BeKult, Sarah El Miniawy Hefni, and Cargo records. I don’t want to rush, I want to experiment and try out new things and we’ll see how things go!

AC | When you launched your own career, did you try to approach other labels or get signed yourself?

KA | Not at all. I’ve been part of the music industry from various different angles since 1998 – education, work experience, etc.I [have] gotten to a point where I’m essentially super inspired by people like Frank Zappa, Mike Patton, Ian MacKaye from Fugazi and Dischord records, people who have maintained control of their own works and done things on their own terms. This is always the way I’ve wanted to develop my own work, and I want to be able to raise my children from my music. Independence is the only way for me.

AC | What did you learn from your indirect experience of labels and indie labels in the Arab World?

KA | This is a very interesting question because there has been a handful of labels that have started. Some have done very well, some have managed to stay very sustainable, and others have had to close down. There are many reasons for this, plus the political climate doesn’t help. What I learnt is that there’s still a long way to go and a lot more experimentation needs to be done. What you find a lot of the time is that people either work based on a very indie local model, or on a very commercial model. What’s missing is this place in between that merges elements of both, and that’s what I want to try now. The music industry has changed; there are more tools available thanks to the internet, and our voices are now being heard a little more in the Arab world. Audience numbers are much bigger than what they used to be, because of all the work that people like Ruptured, Al Nihaya, Al Maslakh and Forward Music [have done] in Beirut, that Eka3 has done in the past five years in Cairo, Amman, and Beirut, and Tony Sfeir's work Incognito in the last five years. The results of all of that hard work are starting to bear fruit now, and I want to be part of that movement in some way.

AC | You said that you want to position yourself between the two extremes of the commercial label and the indie label so how do you see Nawa records?

KA | I hate major labels, [and] I hate the mentality.

Khyam performing with Alif Ensemble. Photo: Lars Opstad

AC | So it’s an indie label?

KA | Of course it’s an independent label! It’s self-financed and works with those kind of indie principles in mind. I know it’s kind of a cheesy thing to say as well and it has become very charged since a long time. Over the years I’ve heard about [many] indie labels that treat their artists very badly, but there are [some] indie labels that treat their artists very well; [particularly] labels that were artist led, that focused on these kind of small communities. [For] example, Mike Patton’s label Ipecac, [they] launched with two artists, Fantômas (one of Mike Patton’s solo projects), and the Melvins. The Melvins have been around for over 30 years, and suddenly you saw this small group of people who have had a really long history in the music industry working together as a tight knit group and creating something. Ian MacKaye from Fugazi started Dischord records in the 1980s [as an outlet] to release Fugazi’s music and help them remain independent and self sustainable. He opened [it] up to other artists as well and created an entire genre of music around it. Hydra Head [was also] started by guys from a band in the early 1990s. Hydra Head was a small and close knit group of friends helping each other release records, remain sustainable and independent, and the results of that label were amazing – [many bands on it were very successful.] The examples are many. Einstürzende Neubauten from Berlin were signed to Mute records for a long time, Mute being one of biggest indie labels in the UK at the time. In 2001, Einstürzende Neubauten went alone, and they were one of the first bands to do a fan funded album. In the end, they ended up resigning with Mute but on a licensing basis. Mute stopped being the owner of their work so they managed to regain their independence and control over their work. These are really important points and this kind of discussion doesn’t really happen in the Arab world, since there are too many other things to think about [before hand]. As artists we should be aware that we have rights, we can control our own works, distribute [them] professionally, efficiently, and at reasonable prices for our audiences, while being able to make this kind of plan for self sustainability. We can’t sit around relying on funding from arts councils or grants for the next ten years.

AC | I know that you have lots of different musical influences and like many different types of music that you like, but is there one defining artistic vision that you have for artists that you want to work with?

KA | Honest music and honest art, that’s the main thing that has always really attracted me, whether it be cinema, literature... anything that is someone's honest vision, their expression of something they really feel. [I want to work with] people who have artistic integrity, a clear artistic vision, and are hard working. I work hard, so I need to make sure that I’m working with people who are prepared to put in the effort at least as much as I am.

AC | And how about the geographical radius?

KA | I don’t care about geography anymore, all of this stuff doesn’t mean anything anymore!

AC | Since when?

KA | In the last couple of years [mainly]. The more I travel, the more I see, the more I experience, the more I just don’t care. I’m not saying let’s erase borders and [build] cultural bridges and all this kind of new age bullshit, it’s really about [the] love of life. At the end of the day, it makes no difference to me if someone is from Zimbabwe or from Ramallah.

AC | So you wouldn’t be able to define a geographical radius for the work of Nawa?

KA | Well, I want to be working with new music from the Arab world, and I want to encourage artists and help them produce new works. I want to encourage production in the region, through releasing new music, getting people to create new works, and helping get those works out, as well as some reissues for the sake of documentation.

AC | You said new music from the Arab world, is that less charged than “alternative music”?

KA | It’s less charged you’re right. I don’t want to label things because I don’t want to be working with artists who are in one specific genre. That’s never been something that attracts me, because there’s all kinds of genres and amazing music that appeal to me. There is so much happening, from weird noise to rock and metal, to you know, alternative classical Arabic stuff with a bit of a new twist, electro chaabi stuff, there’s all kind of like weird rock happening and I just think it’s amazing but one thing that the artists are missing out on is this idea of self sustainability, and that’s what I want to try and develop with artists because it’s really necessary. Otherwise we’re going to get to two or three years - and I’ve seen it happen a million times in London - where people work so hard and they’re so enthusiastic about the music that they’re making, but in the end they need to earn a living and so many of them stop or just slow down. Stars in Battledress for example [have] only just released their second album, and their first we released on House of Stairs in 2003! That's eleven years! I don’t want us to fall into the same trap. Everything has changed, it’s harder work, but achieving things is easier, it’s a funny paradox. You have to work much harder because there is this kind of saturation of music, so you have to work much harder to be heard and and to make your work available, but paradoxically, the tools to do those things are far more accessible so it’s a balance between the two.

Photo: Leif Molsen

AC | In terms of targeting audiences, when I was speaking to Tamer Abu Ghazaleh, he was saying we want to develop an Arab scene, and an Arab audience. Are you also thinking about these kinds of boundaries?

KA | No because I want Europe, North America, Latin America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand to hear it! I don’t care about these confines anymore, but of course my energies are going into the region because I want to be able to continue developing this direct relationship with music fans that are there. They’ve supported us so much in the last few years, and in a way it’s my way of saying thank you by making these works available to them. This however, won’t detract from the focus on Europe and making the work available in Europe, and for performances to take place everywhere.

AC | Since you’re only working on a licensing basis, it also shares the load with the artist who can then promote his work through other medias?

KA | Yeah kind of. Obviously it’s an exclusive licensing, but the point in that is that the artist maintains ownership, meaning that once the contract with Nawa is finished (and it’s not a very long contract), they’re able to move onto another label, reissue the album themselves, and [basically] do anything they want. They own the work 100 per cent, and I’ve been very careful to get this idea across and to make sure that everybody is aware of it. There are many things that happen in between the lines in the music industry, with contracts and intellectual property. The more research I do, the more I realise that we need to be really careful as artists to have control over our works – how it is presented to the public and how it’s shared with people and represented. The issue of representation is huge. We’re constantly fighting that battle. In the Arab World and outside, since 2011, everybody wants to use the word revolution in every other phrase, and you know, people have already started saying things like “a revolutionary label” about Nawa. It isn’t revolutionary, it’s quite the opposite! Nawa is doing [things] that have been tried and tested for [over] 20 years! We’re not here to sell a product to people, we’re here to make something available.

AC | But that’s the problem because you also have to be viable and sell the art?

KA | Things will sell. The thing that people forget is that we are small independent artists dealing with a small kind of niche fan base. The people who want to hear these albums and who want to support these works are there. The more people that get on board the better. I mean we need to sell albums, to have this exchange, but we’re taking an independent route as opposed to relying on a boss. We’re our own bosses and that’s how we like it. This is our product, our product is our work, whether it be a live concert or a record and we obviously need that financial support to be able to live, and to reinvest in future works so we can expand and so people don’t hear the same stuff over and over again.

AC | I was wondering if the launch of Nawa had a link with the work of Eka3 who you’ve been working with and if you wanted to take it from there and create the label that it initially wanted to become?

KA | Actually no, Eka3 is kind of split into three areas, one is sync licensing, one is tour booking, and the other is a label. It’s going to be a new label called Al Mustaqil, so that’s happening for sure. Tamer is a very close and [dear] friend, [and] we’re trying to find the best ways that we can work together, because at the end of the day, I wouldn’t have got to the level that I got to in these last couple of years without Tamer or Eka3's help. They’re the ones who helped me do all the touring in the Arab world, who helped me reach out to that fan base, but this is a personal dream that I’ve been [wanting] to do for a long time, so that’s why I launched it. We’re going to try and work together as much as possible, and develop as much as possible, because we’re friends and we’re all part of the same wave. Even if we have completely different outlooks on the way things should be done – I mean we argue all the time – but there’s so much respect and love there – we’re brothers! The same with Maurice, with the the guys in Alif, with Beirut and Beyond, the guys from Irtijal festival in Beirut, Sherif Sehnaoui, Rupture records, Ziad Nawfal, Tunefork studios... everyone! We’re all part of the same thing, we’re all independent [and] we all have our own ideas!

“Benhayyi Al-Baghbaghan (Salute the Parrot)” cover art

AC | Do you really feel that spirit among this group of actors that you are part of?

KA | I feel that spirit from everybody, [and] I don’t feel any competition with [them]. I don't intend [to be] competitive in any shape or form whatsoever, the beautiful thing about what’s happening is that everyone has his own vision, there is a lot of individuality, and for me this is the most exciting thing. Mahmoud Rifa’t has a very specific vision for 100copies, it is a very specific kind of label, its name denotes the kind of vision that is has, and now he’s opened a studio and a small venue, and doing all kinds of things in Cairo such as shows and [organising] a fantastic festival. Tamer set up Eka3 with a very specific vision, and that’s what he’s been working so hard to develop for the last five years. Sherif Sehnaoui and Ziad Nawfal [put so much effort in] al Maslakh. Everybody works hard to [accomplish] their specific visions. It's all about individuality, dreams and visions, and I [love that]. We’re all working with the same fan bases basically, [similar] audiences and goals in mind, so why not? The more we can work together, the more people are going to benefit from that.

AC | From talking to most of these people, I feel that although they might have individual visions, it seems that they all work towards a common purpose: it’s about developing opportunities, and allowing artists to be creative in the Arab World.

KA | Exactly! What Sherif Sehnaoui has been doing in Beirut for the last fourteen years with the Irtijal festival has been absolutely phenomenal. He has managed to sustain a festival that deals with really weird avant-garde noise experimental music in Beirut for [a long time]! That is not a small feat and that does not happen without hard work. I love what they do, and every time I can I attend, I do. He invited Maurice [Louca] and I to do a show together last time, [and] he treated us with so much respect. [Knowing people like Sherif] makes me want to try and develop things as much as possible, if there a possibility to do co-releases in the near future we’ll do it, [or] trying to organise tours with everybody, anything that can make our lives easier I’m up for it. I really respect and admire [all those guys] and the things they do.

AC | Do you think it’s still a niche market, a growing niche or is it becoming sustainable?

KA | We have reached a point now where a lot of what we have been dreaming of is actually happening, so we need to react to that, not only in an artistic sense but also in a professional sense. We need to start organising ourselves, making sure that things are planned in advance better, etc. I believe we all learnt a lot through [our] experiences [and] now it’s time to learn from our mistakes. I think it’s becoming sustainable, it’s definitely still niche because the numbers are small in comparison, but you can’t compare the audiences we’re working with the audiences Rotana is working with. It’s impossible!

AC | How optimistic are you about the development of new Arabic music?

KA | There is no question about it, there has been a movement happening for the last ten years and only now there is some light being shed on it due to the political circumstances. It’s an amazing movement that has been powerful, and it’s only going to get better, so I’m really optimistic, but at the same time, I think we all need to be careful to make sure that we are thinking ahead a bit more than we used to, and really try to focus as much energy as possible on this idea of self-sustainability. I would hate that in two years time, some of these great artists have to turn around and find a day job because they can't afford to live off their work. This is my nightmare, I’ve seen it happen often and there is nothing that hurts me more.